Charleston Area Medical Center (CAMC) has a long history of performing minimally-invasive surgeries and that tradition continues with the transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). CAMC was one of the first in the region to offer the minimally-invasive procedure in 2013 and recently completed its 500th procedure.

TAVR is performed to treat aortic stenosis – a condition that is caused when the valves that pump blood from the heart become thick and stiff, limiting the amount of blood pumped out.

“The condition can cause decreased blood supply to the brain, lungs and heart vessels,” said Aravinda Nanjundappa, MD, an interventional cardiologist at CAMC and professor of surgery with the WVU School of Medicine Charleston Campus. “This is a progressively deteriorating condition, and in two years if it’s not treated, there’s a 67 percent risk of death.”

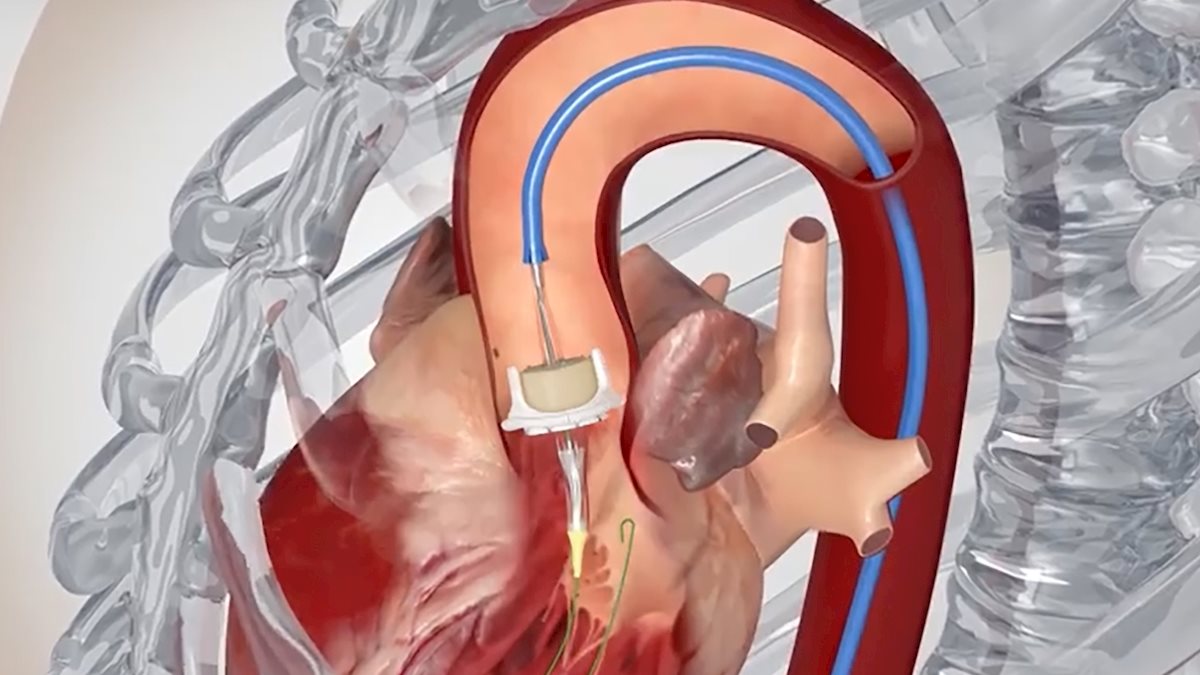

The technique allows physicians to perform what would be a complex, open chest procedure through a small incision in the groin. During the procedure, a synthetic valve is implanted in the heart through a small catheter, usually inserted through the femoral artery of the leg. Once the incision is made, the valve is delivered through a catheter that runs to the heart on a collapsed balloon, which is then inflated to implant the valve. Once placed in the heart, the new valve helps improve blood flow.

“TAVR is less invasive than open heart surgery, so patients can typically be discharged sooner and recover more quickly,” Nanjundappa said.

CAMC’s structural heart team focuses on treating patients with valve-related conditions (e.g. aortic, mitral, tricuspid valves). The multidisciplinary heart team includes cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons, anesthesiologists and coordinators who take a team approach to assess each case and the best course of action.

CAMC’s structural heart team focuses on treating patients with valve-related conditions (e.g. aortic, mitral, tricuspid valves). The multidisciplinary heart team includes cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons, anesthesiologists and coordinators who take a team approach to assess each case and the best course of action.

When the program started in 2013, the structural heart team performed 15 to 20 TAVR procedures a year. “Last year, we did about 140,” Nanjundappa said. “And this year, we are slated to cross the line of 200 valves per year.”

When they were first being performed, TAVR procedures were only approved for patients who were deemed “high risk” for surgical complications, such as advanced age and poor health. However, thanks to advancements in technology and new scientific research, doctors are now able to perform the minimally-invasive surgery on patients who are high-risk and even moderate-risk.

“To know we can extend this to many more people than we could before, we can prevent them from having their chests cut open, and we can give them the option to go home the next day is wonderful for patients and for us,” said Megan Wood, NP, structural heart program coordinator.

“This is a procedure that is instantly rewarding for both the patient and physicians, who feel good because they’ve made a difference for their patients, improved their quality of life, given them a better ability to walk and breathe, and prolonged their life expectancy,” Nanjundappa said.